Humanity is headed toward a cliff, and we have no choice but to change course.

People of different political persuasions fight endlessly about exactly what's wrong, and what we should do to fix it, but I think most of us agree, something needs to be done.

Here are the issues I personally am most concerned about:

-

Government inefficiency and corruption. Almost no government is truly representative and democratic, many are outright authoritarian, and basically all have serious problems with waste, sluggishness, and graft.

-

Police unaccountability and systemic injustice. Crime and punishment in almost all societies is an expression of class power structures rather than the democratic will to defend everyone's rights.

-

Economic inequality, consumerism, corporatism. Our economies are dominated by massive corporations, who instead of creating prosperity gain power by finding and exploiting vulnerabilities, such as those in political institutions, human psychology, or market dynamics. Using the leverage of cumulative advantage these companies slowly form oligopolies and control an ever increasing share of technology and resources.

-

Climate change, environmental destruction. Erratic and severe weather patterns are already beginning to disrupt communities and create increased resource uncertainty. We routinely destroy natural resources that both underpin our planet's economic value and are irreplaceably beautiful.

-

Misinformation, disinformation, surveillance capitalism. It is now trivially easy for any group with spare resources to pollute our shared information ecosystem with misunderstandings or outright lies. The structure of attention capitalism rewards these kinds of behaviors and increasingly addicts us all to a world of shallow entertainment and consumerist indulgence.

-

Resurgence of fascism and authoritarianism. The success of various social justice movements around the world and increased economic instability have empowered a new wave of reactive fascist movements, and many governments have eagerly adopted technological methods of surveillance and control. Violent and irrational forms of market and social fundamentalism have been deeply inculcated into many populations.

-

New technologies and future uncertainty. The increasing reality of incredibly powerful technologies such as strong AI or widespread bio-engineering have caused many to fear about the continued existence of our society, let alone its continued health and happiness. As our species builds ever more dangerous technologies here on earth, and as we begin to venture out to the stars, we have more and more cause for concern.

You're welcome to disagree about the details of those fears, but you don't have to look far to find strong evidence for all of them.

- "Climate change already worse than expected, says new UN report" - nationalgeographic.com

- "Yes, There Has Been Progress on Climate. No, It’s Not Nearly Enough" - nytimes.com

- "Amazon deforestation in April was the worst in modern records" - newscientist.com

- "There's never been such a severe shortage of homes in the U.S. Here's why" - npr.org

- "Water privatisation: a worldwide failure?" - theguardian.com

- "How Much Longer Can This Era Of Political Gridlock Last?" - fivethirtyeight.com

- "Report: Corruption in U.S. at Worst Levels in Almost a Decade" - foreignpolicy.com

- "Democracy under Siege" - freedomhouse.org

- "Municipal Broadband Is Restricted In 18 States Across The U.S. In 2021" - broadbandnow.com

- "Every day, we rely on digital infrastructure built by volunteers. What happens when it fails?" - fordfoundation.org

- "Overlooked and underfunded: neglected diseases exert a toll" - nature.com

- "Overpatented, Overpriced: How Excessive Pharmaceutical Patenting is Extending Monopolies and Driving up Drug Prices" - i-mak.org

- "Americans agree misinformation is a problem, poll shows" - apnews.com

- "64% of Americans say social media have a mostly negative effect on the way things are going in the U.S. today" - pewresearch.org

- "Has Wealth Inequality in America Changed over Time? Here Are Key Statistics" - stlouisfed.org

- "Global Extreme Poverty" - ourworldindata.org

- "AI safety technical research" - 80000hours.org

- "Problem profiles: Space governance" - 80000hours.org

How can we possibly solve all these problems? Each of them individually would be incredibly dangerous and destructive, but they overlap in devilish ways. Each reinforces and exacerbates the others, tying the whole collection into a paralyzing Gordian knot. This is impossible right?

I don't think this is impossible, quite the opposite. I think the intertwined nature of these problems isn't an obstacle, but the secret to solving them all.

I am convinced these problems are all coordination problems. They have arisen because we lack effective tools to help us work together and resolve conflicts.

To show you why I'm convinced this is the case, let's first ask this question: why is our current democracy so broken?

Our current democracy is broken because of Plurality Voting

When most of us hear "voting" or "election" or "democracy", we mistakenly assume the method called Plurality Voting must be involved. Plurality Voting is the very simple method where each voter only gets to vote for one candidate.

There are many other ways to conduct a vote or make a democratic decision! As simple and intuitive as Plurality Voting is, Plurality Voting is awful. Many researchers are convinced the only voting method that is both as simple and worse is random chance! If we're trying to create a functional and prosperous democracy, we're using the wrong tools for the job.

Why is Plurality Voting awful? Mostly because it has irrational outcomes when there are three or more candidates. Plurality Voting is effected by the spoiler effect or "vote splitting", where the winner of an election is changed by non-winning candidates entering the election.

Elections are extremely important, so a toxic and irrational voting method will tend to produce a toxic and irrational country.

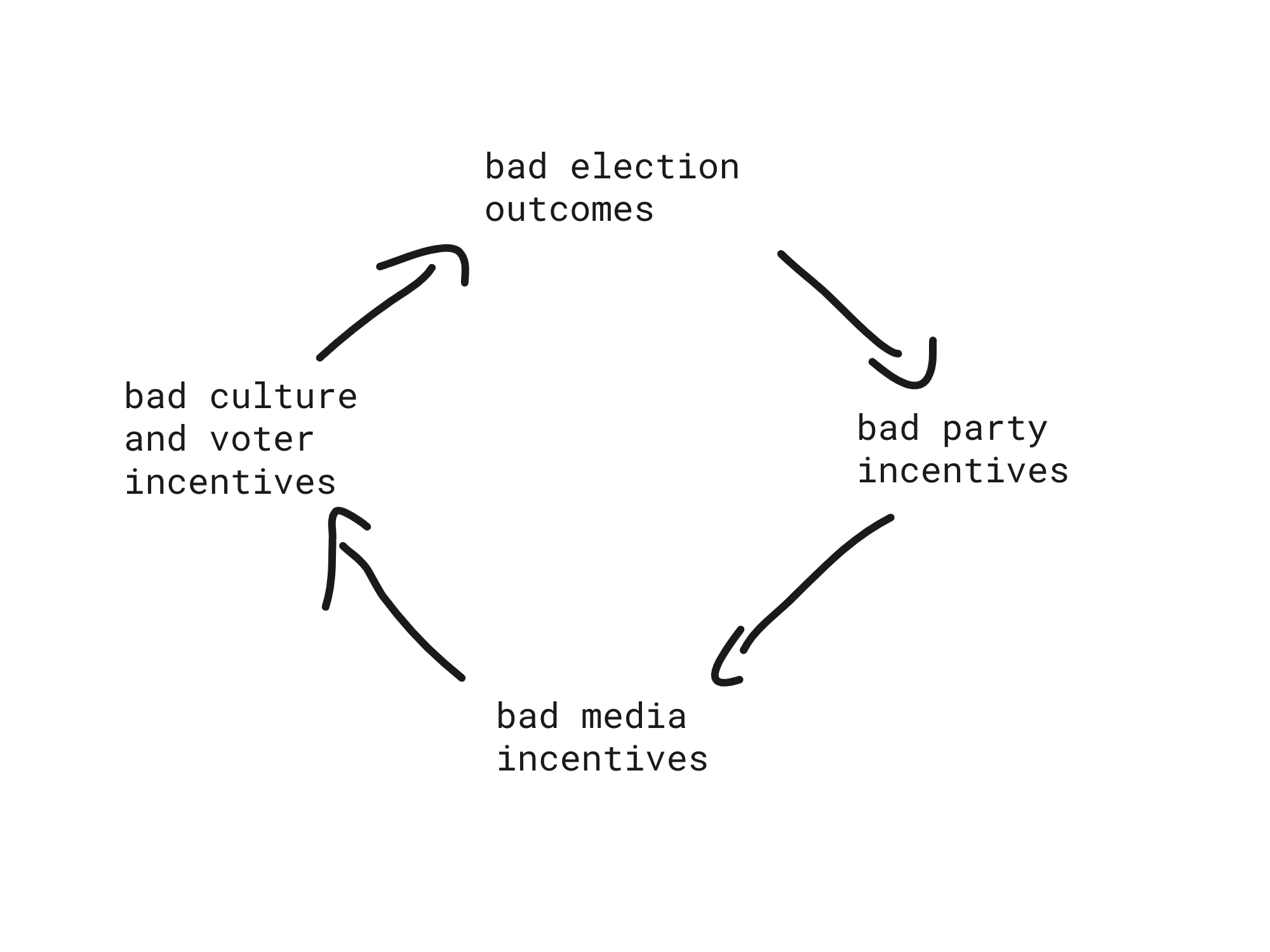

- If the spoiler effect is allowed by the voting method, political parties are incentivized to somehow enforce a two-party system. Otherwise election outcomes will be completely unpredictable, a party can never consistently win elections, and it will slowly die.

- If there are only two parties they need to be very different from each other in order to have a place in the political "market". So they drift to more extreme opposing views and polarize every issue.

- For-profit media companies have to appeal to an audience somehow, so they align with political parties and participate in and exacerbate extremism and polarization.

- Voters can only have a relevant political voice if they somehow "get on board" with one of the polarized parties, so they have a reason to lie to themselves and polarize their own beliefs.

- Polarized voters tend to further polarize parties and media, and the cycle starts all over again....

And of course there are other problems. Go read the voting methods detail chapter if you're interested in a deeper exploration.

Here's my main point: Plurality Voting is awful because of its mathematical structure. Structure determines function, in physics and biology and logic/math. If you use a structurally bad voting system, you will get a structurally bad political entity.

We can solve this problem by designing and using better coordination systems.

Coordination Systems

Cooperation is humanity's superpower.

From the very beginning of our history as hunter-gatherers, the capability that set us apart from other animals was our ability to work together to achieve shared goals. It's not that we could cooperate (many other animals cooperate in many ways), but our ability to pursue complex cooperation, to encode arbitrary information and plans in language and then act using that information.

All our modern prosperity is rooted in our ability to cooperate. The achievements of science and technology are only possible through cooperation. Passing down a culture is an act of cooperation that can continue for many generations. Our complex societies are made possible using governments and organizations that help us cooperate more effectively.

But as much as we've empowered ourselves using complex rules for cooperation, we don't always get it right, as shown by the Plurality Voting problem. Political systems can just as easily be designed by accident or convenience (or malice or greed) as by careful logic. Frustratingly, no existing political system has managed to scale democracy.

Democracy simply means giving all members of a group an equal amount of decision-making power, and many people believe such a thing isn't even possible at scale. So in practice we end up with creaky hodge-podges of fairly arbitrary rules that are easily exploited by small cadres of insiders and never seem to operate fairly, efficiently, and in the best interest of all.

We don't need creaky and arbitrary rules cooked up by politicians hundreds of years ago.

Coordination systems are just algorithms, which means they can be improved.

The term algorithm has taken on a spooky quality in the era of massive technology companies, but the concept isn't inherently dangerous. An algorithm is just a list of instructions intended to produce some outcome. All of us use algorithms all the time, such as when we cook a recipe or do some specific exercise routine. Voting systems are just algorithms.

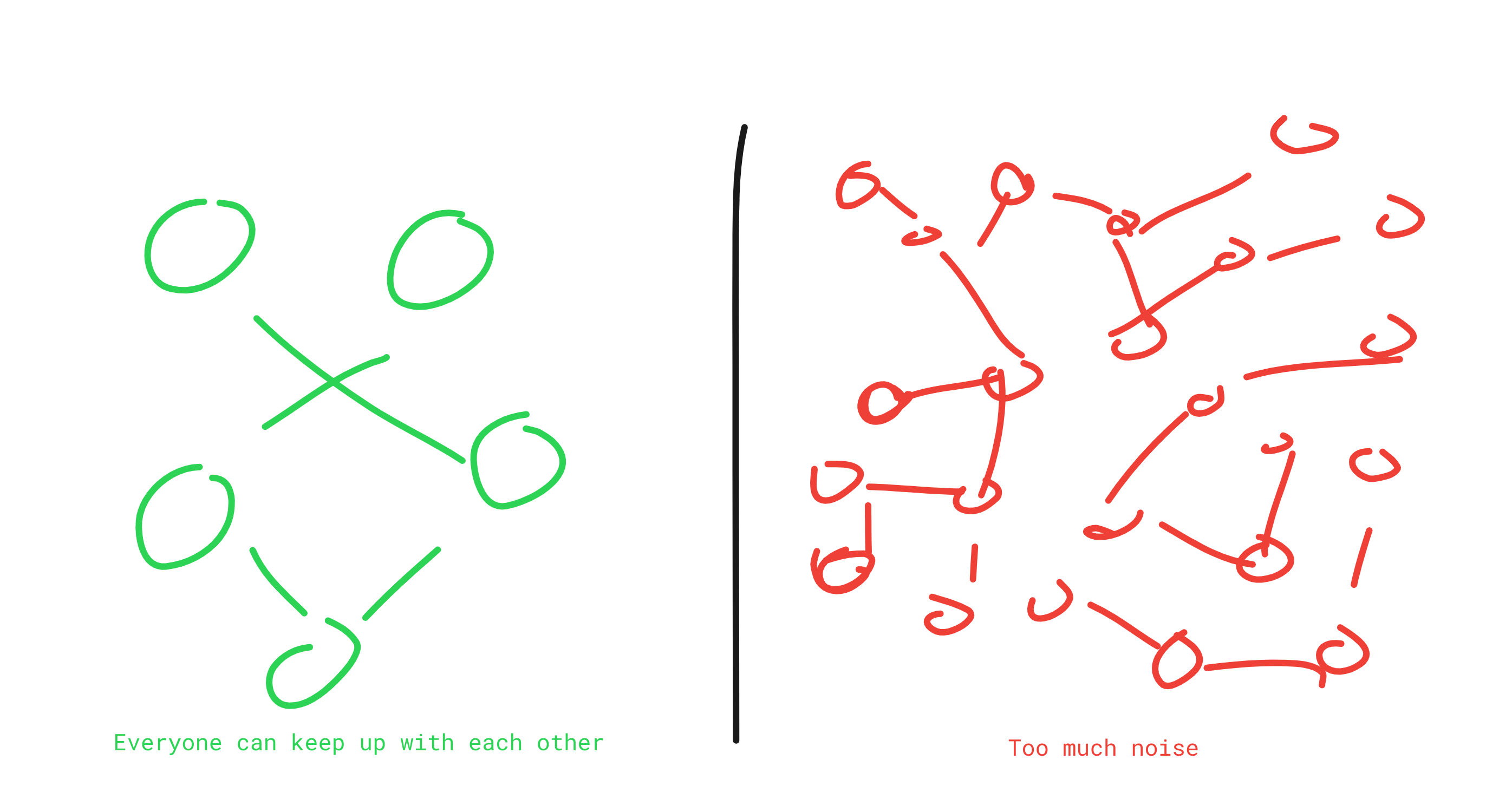

For small groups of people it's usually possible to reach an acceptable consensus just by reading each other's emotions and talking and listening. But when too many people must be involved in a decision, there's too much noise and we can't possibly follow our natural algorithm.

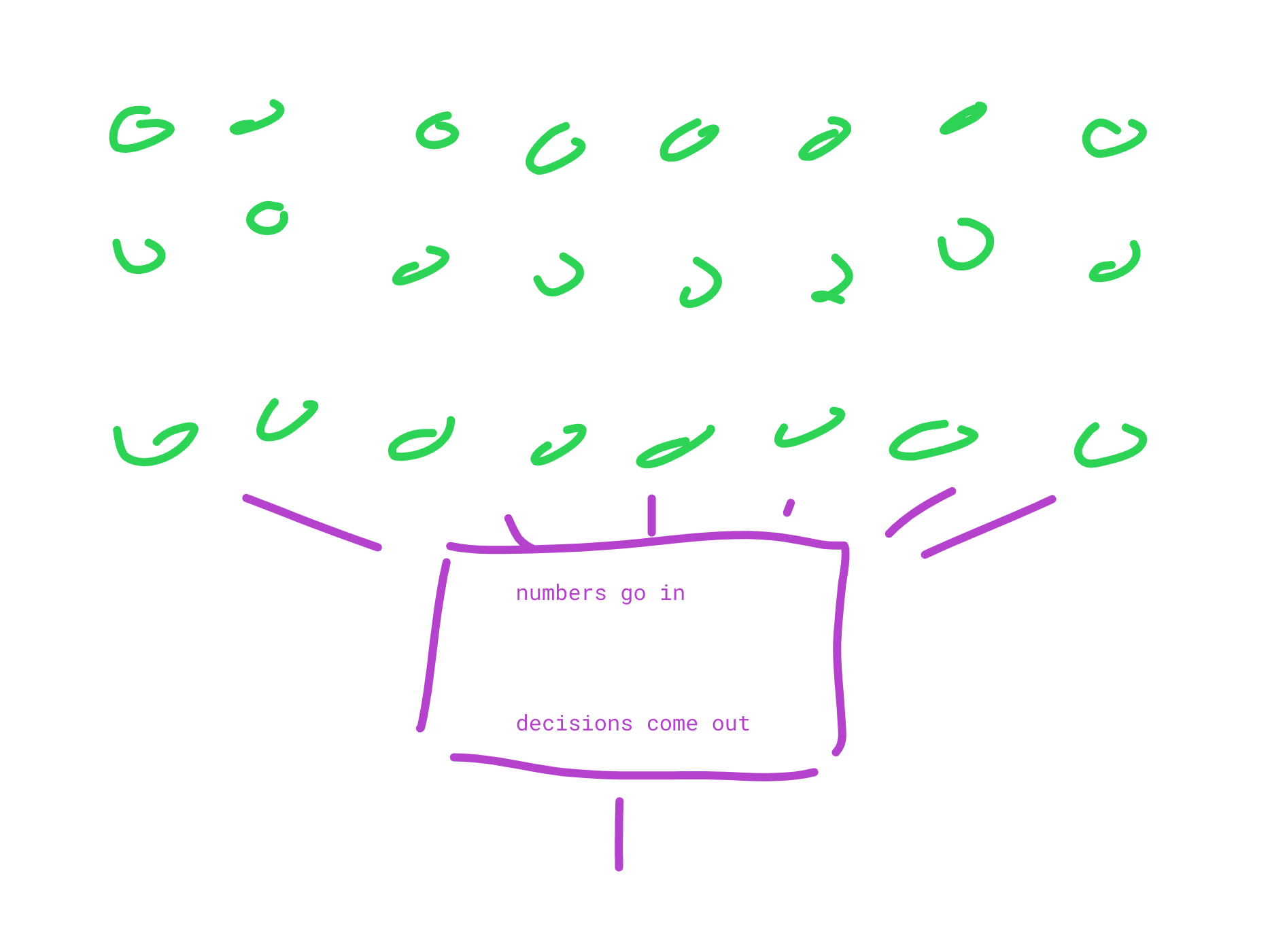

Voting systems were invented to solve this problem. Since we can't extensively interview every single voter, understand what they want, and easily combine everyone's preferences into a decision, we simplify the process. A voting system presents each voter with a discrete list of options to choose from and adds up the votes.

Since voting systems are just algorithms, they have a precise mathematical structure that can be studied. This means it's possible to prove things about an algorithm with the same certainty we know 1 + 1 = 2.

It's possible to prove one algorithm is superior to another in some way (sorting a list of items this way is faster than that way). It's even possible to prove an algorithm is optimal in some way, meaning it's impossible to do better in that particular way (stacking incoming items in this way is the best you could possibly do).

This means it's possible to design better coordination systems. Academic fields such as political economy and game theory study these questions, and try to come up with systems that perform better in different ways.

Math and logic aren't all we'll ever need of course. Logical theories can only reason about imaginary models of the real world. While they can help us avoid wasting time on clearly flawed experiments and point us toward possibilities we would never bump into with experiments alone, we still need to perform experiments to see if our imaginary logical models usefully align with reality.

But this realization still offers us a hopeful path, that our problems are less devilishly tangled than we thought. It's possible for us to use the same tools we've used for thousands of years, logic and experimentation, to get ourselves out of our current mess.

I was first introduced to this possibility when I encountered Aaron Hamlin discussing Approval Voting and how it could dramatically improve our democracy, and Glen Weyl discussing Quadratic Voting/Funding and other ideas espoused by the RadicalXChange foundation. Before hearing these scholars, I thought it was just unavoidable for a democracy to be a toxic mess. They opened up my thinking and helped me realize it's possible for us to implement democracy better. I was excited about Hamlin's and Weyl's ideas, and I learned as much as I could about them and other related ones.

But I slowly became convinced no one had fixed the problem enough. No one had presented a complete system for coordinating a democratic society, one that had the flexibility to allow an arbitrarily large group of people to cooperate without the need for creaky arbitrary rules and cadres of insiders.

This book presents a structure I think could act as the foundation of such a complete system, called Adaptive Democracy.

Adaptive Democracy

Adaptive Democracy uses a different paradigm of voting, called Adaptive Voting, which isn't a voting method, but a different way of thinking about voting entirely. Adaptive Voting could allow truly flexible and scalable direct democracy, such that we could abolish the concept of politicians entirely and allow any size group to democratically coordinate in arbitrarily flexible ways. A few key concepts make it so promising:

- Elections aren't time-limited events with arbitrary deadlines, but instead voters have a supply of voting weights they can move around at any time.

- Voters can vote more strongly for issues they care more about, or vote against things they dislike even when they aren't sure what the right answer is.

- Voters can potentially vote directly for any societal decision, even documents like the constitution or tax code, without being overwhelmed by millions of decisions they don't care about.

This book exists to fully explain Adaptive Democracy, to explore the ways it can be used to combine, evolve, and generalize many different coordination systems, and plot a practical and realistic course to actually use it.

Whenever I speak with idealistic people about the world, I almost always find them in a state of despair. Many have thrown up their hands and given up even trying. I can't help but sympathize. The obstacles ahead are overwhelming, and most aren't our fault.

But here's the thing: we don't have any choice. If we don't solve these problems, they will steadily dismantle our society, and possibly destroy us entirely.

We have the obligation of hope. If we don't, perhaps arrogantly, assume we can figure it out, overcome these challenges, and make a better world, then our failure is a foregone conclusion. We have to start asking how we can solve these problems, not if we can solve them. Adaptive Democracy and this book is my first contribution, and a gathering point I hope will inspire others.

Overview of this book

This book isn't structured in the typical way. Since a discussion of coordination systems can easily get extremely wonky and detailed, this book is structured like a tree with many small branches rather than a typical "straight line" book. There are only four main chapters, meaning pretty much anyone can get the big ideas in a single sitting. All chapters freely point to other "detail" chapters for those interested. The book is published as a website to accommodate the tree structure.

This book is open source, and a work in progress. This "tree" will continue to grow. Anyone is free to suggest edits or additions by submitting a pull request on the book's online repository.

Here are the main chapters:

- Adaptive Democracy discusses the central concept, how it can enable direct democracy, and some important details it needs to work properly.

- Common Resource Rights discusses how Adaptive Democracy can be blended with Harberger taxes to both maintain the useful aspects of private property without allowing continued cycles of cumulative advantage, and ensure resources tend to be used for socially beneficial purposes.

- The Power of Cooperatives discusses how cooperatives can use Adaptive Democracy to finally meet their full potential and help us build a fair and sustainable economy without waiting for government reform.

- A Realistic Plan for Fundamental Change discusses how a political party and a consumer cooperative both governed using Adaptive Democracy can validate Adaptive Democracy in the real world and help us slowly take back control of our economies and governments.

The table of contents lists all finished detail chapters. Here are some particularly interesting ones:

- Why is our democracy broken? An introduction to voting methods and their rippling consequences.

- Provably correct software is possible and necessary - Every part of our society relies on software. It can't continue to be unsafe and unreliable.

- Blockchains aren't going to fix society... but Adaptive Democracy and cooperatives could.

Footnote: is Adaptive Democracy provably optimal?

Maybe! I've developed some very rough work-in-progress proof sketches that are convincing enough to start sharing the idea and building experimental tools.

I'm a skilled software engineer capable of immediately building usable implementations of Adaptive Democracy, so it wouldn't be the most effective use of my time to gain the background necessary to create proofs the academic community would actually accept. I hope my proof sketches are interesting enough for daring academics to explore further! Please reach out to me if you decide to do this!